Imagine you are reading a Board or Committee paper, covering progress on a significant, but nebulous project. Launching a new marketing campaign; a new product line – that sort of thing.

How do you know if the project is genuinely on track, and whether management’s proposed next actions are the right ones, especially if it’s one of those initiatives where there’s a “hockey stick” payoff, some way into the future.

Of course, metrics should provide an answer, giving current status and projections, but in my experience, metrics – especially of the forward-looking variety, and particularly with marketing related matters – often don’t give us what we need.

The metrics may seem disconnected from one another, each throwing light on a different aspect of the project, but with no overall illumination. You may not have all the data you require and, crucially, there may be no explanation of the link between management actions and outcomes, in a cause-and-effect sense.

For example, with a new advertising campaign, you might be given metrics that cover: opportunities to see; spontaneous recall; likelihood to consider purchase; inbound contacts via digital channels, branches and call centres; increase in products purchased.

But, if the links that managers assume exist between their actions and the outcomes are not explained; if there’s an absence of interim targets; if there’s limited historic data to help gauge the accuracy of management’s current estimates; it’s just not possible to take informed decisions on next steps.

To exaggerate, but slightly: if spontaneous recall is up X percentage points; if calls to the call centre are up Y percentage points, how much money do you spend on the next pulse of the campaign? It’s impossible to answer properly, without more data and insight into management’s thinking.

In the end, you may have to cross your fingers and trust the experience and expertise of the executive, but then that’s hardly an auspicious basis on which to be spending millions, is it.

On the other hand, and again exaggerating to make the point, if you knew that historically, spontaneous recall at X% led to ~Y% consideration Y weeks later, and of that group, ~Z% contacted the organisation Z days later, then management’s estimation of reaching interim targets (which are 100% guaranteed to be imperfect, let’s not forget), and suggested actions forward can be given greater weight.

The key is to have the executive set out a plan beforehand, that: explains the historic and current data that will be used at each stage of the project; sets out interim targets in a chain that leads from start to ultimate objective; explains the connection between the actions management propose and the impact on outcomes they expect, at each stage. If the actions taken do not lead to the anticipated outcome, you can learn from the experience and adjust the plan.

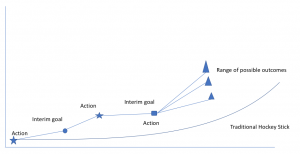

This sort of approach should give you enough information to constructively challenge the executive, and is a better basis for action than a hockey-stick shaped project with a start, lots of disconnected metrics, few interim progress indicators and a hoped-for, glorious finish.

Compare the hockey-stick below and an illustrative alternative, by way of example.

So before the next, nebulous project starts, maybe it warrants a more detailed discussion, to give a shared understanding of cause and effect links, of data to be used to measure progress, of the sorts of interim targets that should be considered and what the areas of ignorance and uncertainty are.

And if the executive cannot provide the level of detail you are looking for, that’s a whole different conversation in itself.

As always, there’s much to do and time is short, so good luck and get cracking.